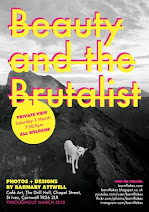

There has never been more interest in brutalist architecture – numerous books are published on the subject; plates and tea towels are adorned with brutalist imagery; there are hundreds of websites and Instagram accounts dedicated to what the French coined raw concrete, béton brut (unfortunately we translated the word rather brutally). Brutalism is the new iconic (iconic once used to refer to Russian icons; now it's bandied around and any celebrity, building, artwork, film or photo can be instantly iconic), a word tossed around to describe any concrete monstrosity.

Its popularity has come at a time, paradoxically perhaps, when many brutalist council estates and buildings are being knocked down. In a 2016 speech former Prime Minister David Cameron pledged to spend £140 million demolishing or regenerating 100 sink estates (which sounds a lot of money but to my rusty maths only equates to £1.4 million per estate). The speech coincided with a bill aiming to reduce the amount of social housing in the country.

Cameron went on to say: "Decades of neglect have led to gangs and

anti-social behaviour. And poverty has become entrenched, because those

who could afford to move have understandably done so... The mission here is nothing short of social turnaround... I believe we can tear down anything

that stands in our way."

There are some brutalist success stories. Flats in the maze-like Barbican estate cost over £1m. The Park Hill estate in Sheffield had a recent award-winning overhaul. But generally what seems to be happening is council estates are being deliberately neglected and then demolished, residents are being moved out of London, and luxury, overpriced (and generally very ugly) apartment blocks are being built on the land, sold to Chinese/Russian/Arab investors for large sums of money and remaining empty most of the time. This is the bizarre solution to the housing crisis? When there's a waiting list of at least 1.5m people for social housing?

The mission here, it seems to me, is social cleansing and making as much money as possible at the expense of the residents of these demolished blocks. As as one ex-resident from the now-demolished Heygate estate said, "We have literally been sold out by our own council". That some residents had lived their entire lives in the area, had family

and social networks and jobs in the community seemed to be of no

consequence. Many of the residents were forced to move out of London (meaning they'll never be able to afford to move back) to cities as far flung as Birmingham. Of the 2,535 new homes built where the Heygate estate was, only 79 were allocated for social renting.

This doesn't seem to concern any of the brutalist websites, bloggers or Instagrammers. Brutalism is cool. Goldfinger and Le Corbusier are hip. On tea towels and mugs, in books, in moody black and white photos. When it was announced the Robin Hood Gardens estate was to be demolished, news that the V&A were to acquire a three-storey section of the block received far more press than the future of the estate's residents. Considering brutalism is usually public housing, it seems strange that the residents are usually completely absent from any imagery.

During consultations (which admittedly I'd take with a pinch of salt), 75% of residents in the Robin Hood Gardens estate said they wanted it demolished, whilst at the same time, the 20th Century Society and high-profile architects including Richard Rogers, the late Zaha Hadid, Toyo Ito and Robert Venturi petitioned to save it from the bulldozers. Britain's "most important" post-war social housing development, enthused Richard Rogers, presumably not having spent more than half an hour on the block (a half-hearted Twitter storm erupted when residents invited him to spent the night on the estate; Rogers said he would, but never did). Residents variously described the 'streets in the sky' estate as a "prison" and "not a home" as the Building Design website were calling it "seminal".

The brutalist debate is a tough one. The buildings have become trendy, but not for most of the residents who live on them and have to endure the crime and neglect. I'm never one to agree with demolition – once it's gone, there's no bringing it back. I certainly prefer most brutalist buildings to the hideous new luxury apartments springing up all over the UK. I say we should keep brutalist estates but invest in them, regenerate them, give them proper lighting, give them a lick of paint (or a mural of a dog)! I lived on one for years, the Alton estate in Roehampton. It wasn't that bad. And Grade II listed, so hopefully it won't be demolished, though the library, which isn't listed, may well face the wrecking ball.

Previously on Barnflakes

The regeneration game

Death of the high street

Modern architecture is rubbish

Alton blues

Elsewhere on the web

dezeen.com is my favourite online architecture magazine.

Saturday, January 13, 2018

Thursday, January 04, 2018

January Tales

Well, I've never owned a car, TV, laptop or microwave oven

(And not just because I'm poor, or stubborn).

I've never even thought about buying a games console, or a Kindle,

Or a suitcase on wheels

(I just don't like the way it feels).

I've never hashtagged or Tweeted

(Neither standing or seated).

But I got this guitar and I learned how to make it talk

(No, that's a lie, it's a line from a Springsteen song).

But I do got a 40-year-old temperamental record player that's in need of constant repair,

Oh yeah.

But I do got a 40-year-old temperamental record player that's in need of constant repair,

Oh yeah.

And to be fair

It's my favourite thing I own

Even if about it I constantly moan.

(And not just because I'm poor, or stubborn).

I've never even thought about buying a games console, or a Kindle,

Or a suitcase on wheels

(I just don't like the way it feels).

I've never hashtagged or Tweeted

(Neither standing or seated).

But I got this guitar and I learned how to make it talk

(No, that's a lie, it's a line from a Springsteen song).

But I do got a 40-year-old temperamental record player that's in need of constant repair,

Oh yeah.

But I do got a 40-year-old temperamental record player that's in need of constant repair,

Oh yeah.

And to be fair

It's my favourite thing I own

Even if about it I constantly moan.

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)